services, or can do so only with limited and often inadequate

resources. Access to care will therefore be a great challenge

to majority of patients.

Within ten years of the MCM programme, national public

awareness campaigns brought down the number of late

diagnoses to 30%-40% from a baseline of 70% (16). The

current national referral and treatment network of 39

paediatric oncologists in 37 hospitals made subspecialty

care nationally available, particularly to poorer patients

outside of Metro Manila, reaching an annual average of

2,553 patient beneficiaries to date from a baseline of only

about 1,000 (16). Treatment abandonment rate was brought

down to 10%-20% from a baseline of 80%, and the currently

available survival rate for childhood leukaemia based on

hospital-based data from participating hospitals improved to

78% from a baseline of only 16%-20% (16). To further

expand services to as many places in the country without

paediatric oncologists, PCMC has now increased the

number of clinical fellows entering first year in the training

programme to four from an initial of two, which together

with one from the UP-PGH are expected to provide in the

next ten years for an adequate number necessary for the

manpower need of the country for paediatric oncologists

who will practice in underserved areas outside the major

cities.

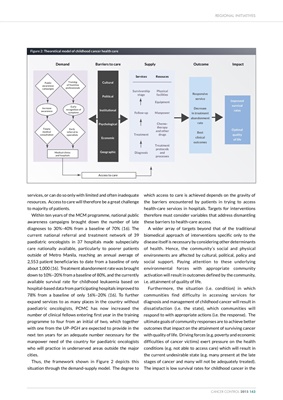

Thus, the framework shown in Figure 2 depicts this

situation through the demand-supply model. The degree to

which access to care is achieved depends on the gravity of

the barriers encountered by patients in trying to access

health-care services in hospitals. Targets for interventions

therefore must consider variables that address dismantling

these barriers to health-care access.

A wider array of targets beyond that of the traditional

biomedical approach of interventions specific only to the

disease itself is necessary by considering other determinants

of health. Hence, the community's social and physical

environments are affected by cultural, political, policy and

social support. Paying attention to these underlying

environmental forces with appropriate community

activation will result in outcomes defined by the community,

i.e. attainment of quality of life.

Furthermore, the situation (i.e. condition) in which

communities find difficulty in accessing services for

diagnosis and management of childhood cancer will result in

dissatisfaction (i.e. the state), which communities will

respond to with appropriate actions (i.e. the response). The

ultimate goals of community responses are to achieve better

outcomes that impact on the attainment of surviving cancer

with quality of life. Driving forces (e.g. poverty and economic

difficulties of cancer victims) exert pressure on the health

conditions (e.g. not able to access care) which will result in

the current undesirable state (e.g. many present at the late

stages of cancer and many will not be adequately treated).

The impact is low survival rates for childhood cancer in the

REGIONAL INITIATIVES

CANCER CONTROL 2015 143

Public

awareness

campaigns Demand

Training

of frontline

professionals

Timely

medical

consultation

Early

referral to

specialists

Increase

awareness

Early

recognition of

symptons

Medical clinics

and hospitals

Barriers to care Supply Outcome Impact

Access to care

Cultural

Political

Institutional

Psychological

Economic

Geographic

Services

Survivorship

stage

Follow-up

Treatment

Diagnosis

Resouces

Physical

facilities

Equipment

Manpower

Chemotherapy

and other

drugs

Treatment

protocols

and

processes

Improved

survival

rates

Optimal

quality

of life

Responsive

service

Decrease

in treatment

abandonment

rate

Best

clinical

outcomes

Figure 2: Theoretical model of childhood cancer health care