these issues are, or have been partially addressed (e.g., half

price bus tickets for cancer patients and free treatment for

children less than five-years old in Tanzania), such funds must

come from the government and are not always available.

Even if families overcome these obstacles, they face the

challenge of extremely limited numbers of nurses, doctors

and pharmacists, and remarkably few cancer specialists

(Tanzania has, for example, a single trained medical

oncologist, no trained paediatric oncologist, two or three

radiation oncologists and perhaps 18 pathologists, almost all

working in major cities).

Access to specialist health services

Unlike other non-communicable diseases, some patients

with cancer are curable through access to earlier and more

accurate diagnosis, specialist consultation and therapy.

Drugs vary markedly in price, even within the same country,

and may sometimes be higher than in the United States or

Europe. This precludes many regimens since most patients

must generally pay out-of-pocket for all diagnostic and

treatment costs. To address this situation, the methods of

education, the division of labour and the delivery of health

services, including cancer services, will need to be markedly

improved. Considerations include:

‰ enactment of equitable policies to subsidize the costs of

care e.g., universal health care;

‰ insurance schemes;

‰ diagnostic and therapeutic co-pay;

‰ increased practical responsibility for medical assistants,

nurses and community health workers;

‰ shortening of training periods for health professionals;

‰ incentivization for practice in rural regions e.g. locating

medical and nursing schools in rural regions, required

rural service periods for health professionals and rural

living subsidies;

‰ re-focusing and re-balancing the mix of academic

(degree-based), discipline/competency-based training

(professional certification) and practical service

delivery.

Medical professional migration

Higher-resourced countries recruit extensively from lesserresourced nations despite these countries having

major

shortages of health workers.3 Concomitantly, although not at

a high level of development, some countries (e.g., India) have

well-equipped and staffed hospitals, generally in the private

sector, that are able to attract patients from high resource

countries for surgical procedures or to provide services such

as interpretations of electronically-transmitted images

(radiographs, etc.). Accordingly, an additional proportion of

the skilled health care providers, already too few to meet

national needs, are lost to their own country. The least

developed countries cannot compete in this market, although

many African doctors choose to work (sometimes to train and

work) in countries with higher levels of development. The

solution is to improve the overall level of care in regions such

as East Africa. This process will proceed much more rapidly

when external educators spend time in countries with

limited development, or at least assist them through

teleconferences, etc. Institution-to-institution collaborations

("twinning") between a high-resource and lesser-resourced

country can be of great value (see article by Raul

Ribeiro), However, international institution-to-institution

programmes are unlikely to promote the building of networks

required to strengthen services across health sectors.

Cancer treatment: Shared care among specialists

and hospitals

Drugs and equipment are of no value without knowledgeable

health professionals, particularly oncologists who can make

treatment decisions and work with a team comprised of

pharmacists, oncology nurses, junior doctors, medical

assistants and social workers. Unfortunately, it can be

difficult or impossible to create such teams when there is no

oncologist to take a leading role. An European Society for

Medical Oncologists survey (2006) reported that only 22

countries of the 39 respondents were able to state how many

oncologists there were in the country and of those who could

provide figures, the number of oncologists per million cancer

CANCER MANAGEMENT

CANCER CONTROL 2014 61

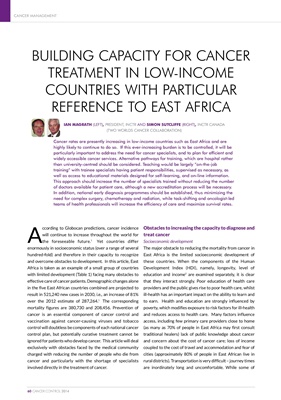

Table 1: UNDP HDI, 2012

Burundi Rwanda Uganda Tanzania Kenya

HDI 0.355 0.434 0.456 0.476 0.519

Rank 178 167 161 152 145

GDP (Current US$, billions) 2.47 7.10 20.03 28.24 40.70

Physicians per 1,000 people ND 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.2

HDI maximum score, 1. Norway's HDI was 0.921 in 2012; GDP figures are for 2012 - UK GDP = 2,476 trillion; UK physicians per 1,000 people = 2.7 (2010/2011); ND = No data